Kitten vaccinations and immunity

Ensuring kittens have an optimal vaccination schedule whilst creating positive patient experiences at the veterinary clinic can be a win-win situation, as Kelly St. Denis describes.

Article

Key Points

Vaccines can and should start as early as 6 weeks of age during the kitten‘s socialization period, giving the veterinary team the opportunity to provide the kitten with early positive experiences.

Feline Leukemia Virus immunization is an important part of the juvenile vaccination protocol, regardless of the kitten’s intended lifestyle.

Booster visits help to ensure immunity, while also providing opportunities for Cat Friendly interactions and the chance to help caregivers understand their cat’s needs.

“First birthday” nutritional consultations promote good health, strengthen the veterinary-client-patient bond, and ensure that patients will return for annual visits.

Introduction

Feline Vaccinology has experienced dramatic shifts over the last few decades. While the infectious agents against which we vaccinate kittens have not changed greatly, in other contexts there has been immense change. There has been progress in our knowledge and understanding of some of these infectious agents and the role of vaccination in their prevention; there have been many changes in recommendations for timing, age and frequency of vaccinations and booster vaccinations; we have additional knowledge about maternally derived immunity and its impact on immunity; the scientific design of available feline vaccinations has changed dramatically; and the approved and recommended sites of injection have been modified. Furthermore, the way we interact with our feline patients has been revolutionized by the adaptation of Cat Friendly principles. These changes make vaccinology in the feline species more challenging to implement but more rewarding than ever before. They also impact all life stages of the domestic cat, with the foundations for immunity and Cat Friendly visits being laid in the first year of life. This article will review vaccination protocols and their implementation for the juvenile pet cat primarily from a North American viewpoint, and the reader is encouraged to seek further detail for all life stages in the recently updated AAHA/AAFP guidelines * [1].

* AAHA: American Animal Hospital Association; AAFP: American Association of Feline Practitioners

Maternal-derived immunity

Maternal immunity, in the form of maternally derived antibodies (MDA), is passively transferred from the immune queen to kitten during lactation. Transplacental transfer of antibodies is not significant in the feline species [2]. The availability of immunoglobulins IgA and IgG to the neonate is impacted by the concentration of the proteins in colostrum, the volume ingested, and the capacity of the neonatal intestine to absorb the protein, all of which are largely time-dependent. The immunoglobulin concentration is highest in the colostrum, with levels rapidly decreasing 3 days post-partum [3]. The neonate absorbs the immunoglobulins primarily in the first 24 hours of life, although evidence suggests that absorption decreases dramatically after only 16 hours [3]. Kittens that do not ingest sufficient colostrum during the first 24 hours post-partum will be at risk of failure of passive transfer, increasing the potential for infectious disease during a period when the immune system is undeveloped.

MDA persist in the kitten for variable time periods, dependent on the antibody titer of the queen and the amount of immunoglobulin absorbed by the neonate. A nadir may be reached as early as 3 to 4 weeks of age [2], although some kittens maintain high levels beyond 16 weeks [4]. While MDA provides protection in the immune incompetent neonate, it is described as one of the most common reasons for vaccine failure [1]. Through a negative feedback mechanism, serum MDA can interfere with neonatal production of immunoglobulins, and its presence can also lead to neutralization of vaccine-delivered antigens, thus limiting the vaccine response. There is therefore a “window of susceptibility” between loss of MDA and development of individual immunity, when the MDA levels may be high enough to interfere with the development of vaccine-dependent immunity but insufficient to protect against natural infection [1]. This window of susceptibility must be considered when developing vaccination protocols for kittens. For this reason, vaccinations against feline viral rhinotracheitis/calicivirus/panleukopenia (FVRCP) have increased likelihood of success if given every 2-4 weeks until a kitten is at least 16-20 weeks of age [1]. The exact interval between booster vaccinations should follow manufacturer guidelines, but a final booster is ideally administered 3 to 4 weeks after MDA has decreased below interference levels, which can vary between litters, between kittens within litters, and with the infectious disease being vaccinated against. Recent guidelines [1],[5] recommend replacing the 1-year FVRCP booster with a 6-month booster against FVRCP.

There is a ‘window of susceptibility‘ between the loss of maternally derived antibody (MDA) and development of individual immunity, when the MDA levels may be high enough to interfere with the development of vaccine-dependent immunity but insufficient to protect against natural infection.

Vaccine concepts revisited – vaccine design

There are numerous commercial vaccines available worldwide that target several infectious feline agents. The 2020 AAHA/AAFP Feline Vaccination Task Force has categorized vaccines against these agents as being either “Core” or “Non-core” based on relative risk and vaccine efficacy and safety (Table 1). Vaccines are designed using a variety of approaches, including inactivated (killed), modified live (attenuated), and genetically engineered recombinant subunit vaccines. Each design is based on different strategies to induce immunity, with the selection depending on many factors including the infectious agent itself, applicable vaccine technology, host immune response, and potential side effects. A basic understanding of these differences, as well as an awareness of which vaccine design is being administered, is critical to understanding the impacts on the patient; these include the type of immunity, efficacy, and potential vaccine adverse events.

Table 1. Vaccination recommendations for pet kittens. Vaccination protocols start as early as 4-6 weeks with boosters administered at 3-to-4-week intervals until 16 or 20 weeks of age for FVRCP, and at 3 to 4 weeks after the initial vaccination for FeLV and FIV.

| Vaccine | First vaccine & boosters (weeks of age) |

|---|---|

|

FHV*-1 +FCV (IN)

|

4 weeks + q3-4 weeks >16-20 weeks |

|

FHV-1 + FPV** + FCV*** (SC)

|

6 weeks + booster q3-4 weeks >16-20 weeks |

|

FeLV (SC)

|

8 weeks + 1 booster at q3-4 weeks |

|

Rabies (SC)

|

12-16 weeks + booster in 1 year |

| FIV (SC) | 8 weeks + 1 booster at q3-4 weeks |

Legend: First boxes: core vaccines: last box: non-core vaccines; IN: intranasal; SC: subcutaneous

*FHV = Feline Herpes Virus, **FPV = Feline Panleukopenia Virus, ***FCV = Feline Calicivirus

Killed vaccines contain inactivated viral particles incapable of setting up an active infection in the patient. Appropriate stimulation of the immune response often requires additional vaccine ingredients, which may include the use of adjuvants. These enhance inflammation at the site of injection, stimulate the innate arm of the immune system, and trigger the necessary immune responses. Compounds utilized in vaccine products include Complete Freund’s Adjuvant, aluminum salts, lipids in water-based emulsions, saponin-based adjuvants, and ligands (oligonucleotides). Response to vaccination with a killed vaccine is primarily antibody/humoral in nature, and such vaccines generally producing a weaker immune response compared with other technologies, with immunity lasting for shorter time periods. More frequent booster vaccinations are likely necessary.

Modified live (attenuated) virus (MLV) vaccines contain viral particles that have partial viability, with a reduced ability to infect host cells. This attenuated viral activity generates an immune response that mimics protection from natural infection, and involves both humoral (antibody-mediated) and cell-mediated immunity without inducing actual disease. The response to MLV is generally more rapid in comparison to killed vaccines. In the absence of MDA, only one dose of vaccine may be sufficient to provide protection.

The most common recombinant vaccines in veterinary medicine contain a gene or genes encoding protein(s) from the infectious agent spliced into the genetic material of a virus from an unrelated species. For example, the gene for the rabies surface antigen was spliced into the Canary Pox Virus to create a recombinant rabies vaccination. The vaccine vector cannot cause disease in the feline species but allows presentation of a targeted viral antigen to the immune system.

Vaccine concepts revisited – adverse events

Administration of vaccinations is a daily practice in veterinary medicine and is generally uneventful and low risk. As the immune system recognizes and responds to the vaccine, minor side effects may occur. This normal immune response includes the release of cytokines which, in mimicking the response to infection, will cause systemic effects such as fever, joint ache, and general malaise. An affected kitten may benefit from symptomatic-based treatment to reduce any ill effects, but the term “vaccine reaction” as applied to these types of natural side effects is ill-advised and can lead to mistrust of the vaccines by the caregiver. Explanation of anticipated natural responses to vaccinations and potential related side effects will assist in alerting the caregiver to these should they occur, will facilitate early treatment, and will avoid causing distrust of the inoculation.

Less commonly, feline patients may experience vaccine adverse events, which may include protracted fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and inappetence or anorexia. The latter may stem from untreated side effects, as described above. In the feline species it is rare to observe severe, acute reactions such as sudden onset vomiting, diarrhea, tachycardia, tachypnea, disorientation and/or collapse. If such acute reactions do occur, it is often prior to departure from the veterinary clinic, but caregivers should be aware of the potential so that the patient can be returned immediately for possible urgent care.

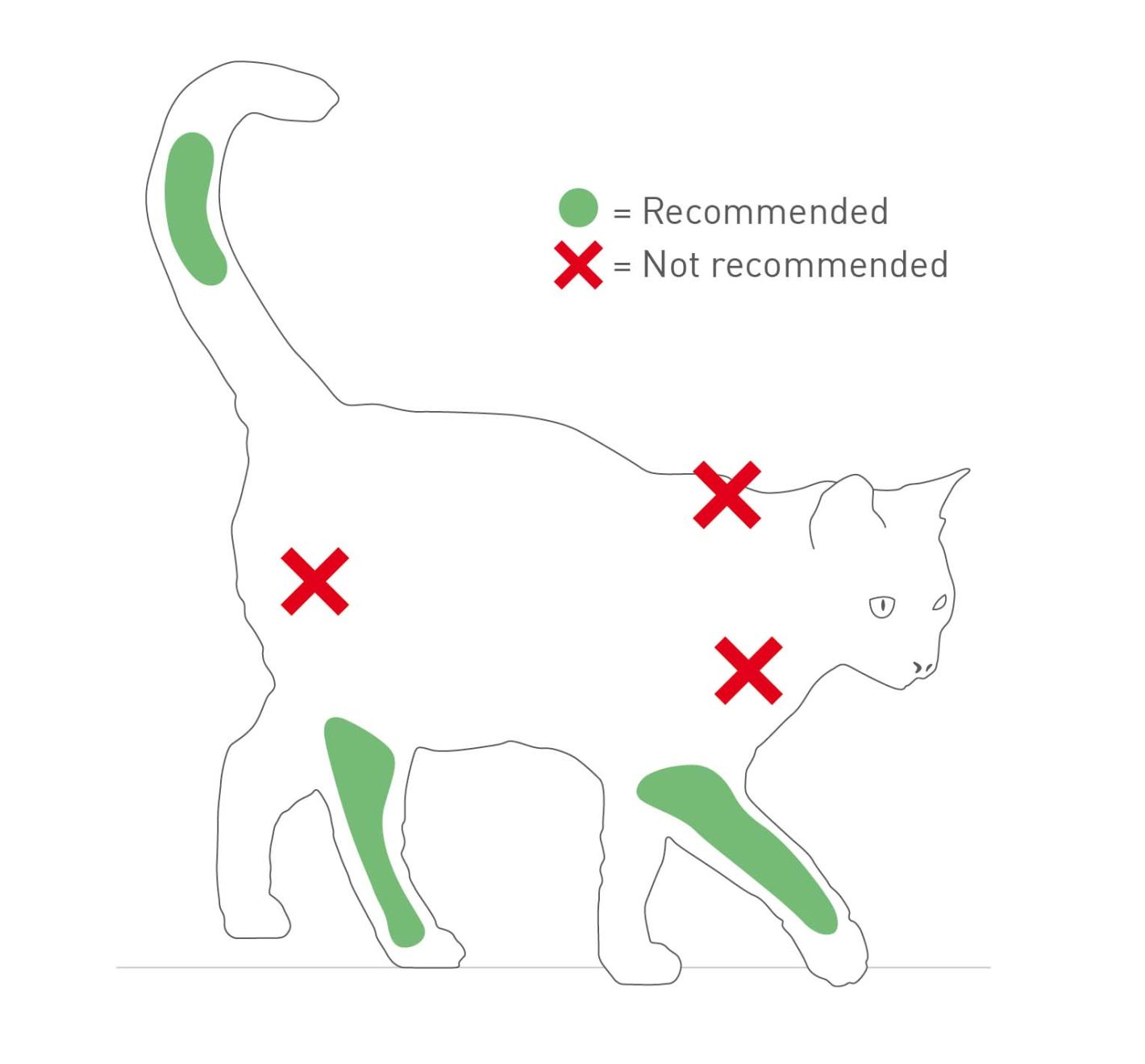

Vaccine injection site sarcomas (VISS) are the most reported cause of feline injection site sarcoma (FISS) [1]. The rate of occurrence is low and varies geographically, and the development of FISS is complex and poorly understood. An inflammatory component at the injection site may play a role, although direct evidence for cause and effect is elusive. There may be a role involving genetic mutations, including those in tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes. The presence of inflammatory adjuvants in certain vaccine types has been hypothesized to be a contributing factor. Causal data remain inconclusive, although anecdotal reports suggest reduced incidence of VISS with the use of non-adjuvanted vaccines. Since FISS are highly invasive neoplasms which can be very difficult to remove surgically, any suspicious swelling or mass at a known or suspected vaccination injection site should be monitored closely. The 3-2-1 protocol provides guidance on how to handle these; a wedge biopsy should be obtained from any reaction at an injection site that persists beyond 3 months, is larger than 2 cm and/or increases in size within one month following injection [6]. Excisional biopsies are not appropriate, as these will most likely miss margins, allowing the locally invasive FISS the opportunity to continue to spread, and making further removal challenging. Surgical excision requires a specific diagnosis and a planned approach that includes two fascial planes. With a lack of complete understanding of VISS etiology, and given the aggressive requirements for surgery, all feline vaccines should be administered below the elbow or stifle, or in the distal tail (Figure 1).

Vaccine concepts revisited – kitten vaccine protocols

Preparing a vaccination plan for a kitten starts with considering the needs of the individual animal. Factors to consider include environmental risk factors, epidemiologic factors, vaccine availability and lifestyle factors. A caregiver may have very specific goals for their kitten’s future lifestyle; this might include status as a single, exclusively indoor cat, it may be living in a multi-cat household with constant outdoor access, or it may fall somewhere in between these two extremes. Whatever the plan, a cat’s lifestyle may well change in the future, so vaccination protocols should be developed with the assumption that exposure to other cats is a likelihood. Even where a caregiver is firm about their goals for their kitten’s indoor lifestyle, it should be recognized that indoor cats are in no way risk-free when it comes to infectious disease.

Developing a vaccination plan must also consider whether a specific vaccine is classified as core or non-core. Core vaccines are those which are recommended for all kittens regardless of lifestyle, including those with unknown vaccination history, and include those which protect against zoonotic disease such as rabies. Such vaccines should offer good protection against prevalent diseases of known significant morbidity and mortality. The AAAH/AAFP Task Force has designated Feline herpes virus-1 (FHV-1), Feline Calicivirus (FCV), Feline Panleukopenia Virus (FPV), rabies and Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) as core infectious agents against which vaccines should be given to all kittens (Table 1). Non-core vaccines against certain infectious agents are those which are considered optional, based on exposure risk, geographic distribution, and the patient’s current and possible future lifestyle. Non-core vaccines include Feline Leukemias Virus (for cats older than 1 year), Chlamydia felis and Bordetella bronchiseptica. Vaccines for diseases which are of low clinical significance or which show a good response to treatment, and vaccines that show minimal to no field evidence for efficacy, or that have a relative increased risk of adverse events, are designated as “not recommended”. Vaccinations currently not recommended by the task force include Feline Infectious Peritonitis Virus (FIPV).

Except for the intranasal FHV-1/FCV (which can be started as early as 4 weeks of age) vaccination should commence at 6 to 8 weeks in all pet kittens. This early start facilitates increased interaction with the veterinary team during the kitten socialization period. The initial FVRCP vaccination should be administered during this first visit. The AAHA/AAFP Task Force recommends administering boosters against FVRCP every 3 to 4 weeks until 16 to 20 weeks of age, with a further FVRCP booster at 6 months when MDA has waned, which is in lieu of the first annual booster. Intranasal FHV-1/FCV can start at 4 to 6 weeks of age, followed with booster vaccinations every 3 to 4 weeks until 16 to 20 weeks of age. FeLV vaccination is considered a core vaccination for pet kittens, and should commence at 8 weeks of age, with a second dose administered 3 to 4 weeks later, followed by a booster at 1 year of age (Table 1).

Rabies is a zoonotic disease with high mortality rates and is a significant public health concern worldwide. Mandatory vaccination of pets against rabies is common in many communities, and the veterinary team will need to consult local legislation to make accurate vaccination recommendations. Timing for rabies vaccinations in the kitten should be based on the manufacturer’s instructions, often starting no earlier than 12 weeks and most commonly at 16 weeks of age. A booster should be administered at one year of age. Beyond this point, vaccines which have been legally approved for an extended 3-year usage can be administered at this interval. Annual vaccination for all other products is recommended.

Retrovirus testing and vaccination

Retrovirus testing is recommended for all newly acquired kittens [7], with additional FeLV and FIV testing recommended at 30 and 60 days respectively following the first test. For ease of use, the second set of testing can be conducted at 60 or more days. The retrovirus status of kittens should be known, with at least one negative test confirmed prior to vaccination against FeLV or FIV. Vaccination against FeLV does not interfere with current standard testing methods, which measure for viral antigen or viral RNA. Standard testing for FIV includes measurement of FIV-directed antibodies, and therefore vaccination will result in false positive testing. This is an important consideration in certain geographical areas such as Australia, where FIV vaccinations are commonly administered, and antibodies generated from FIV vaccines may persist for more than 7 years [8]. The 2020 Feline Retrovirus Testing and Management Task Force recommends follow-up testing for all FIV and FeLV positive cases, using a different manufacturer’s ELISA test or a different test type [7].

Kittens have an increased risk of infection with FeLV upon exposure, with risks declining with increasing age [7] and therefore, as noted above, vaccination against FeLV is recommended for all kittens regardless of lifestyle. Based on current studies, there is insufficient evidence to show that vaccination prevents all outcomes of FeLV infection, however there is sufficient protection to warrant use of the vaccine [7]. Despite assumptions to the contrary, a 2019 Australian study showed that the threat of FeLV in the general cat population in that country was still high, and warranted ongoing testing, vaccination, and appropriate management of potentially infected or known infected populations [9].

The FIV vaccination has limited availability worldwide; however, in areas such as Australia, where FIV has a higher prevalence, the vaccine is still available. In these areas, kittens living at increased risk for FIV exposure (lifestyle, geographical) are recommended to receive the FIV vaccination series wherever possible; this should start at 8 weeks of age, with a second dose 3-4 weeks later and boosters given annually thereafter. Retrovirus status should be confirmed negative prior to vaccination, as false positives can occur as early as a few weeks after first vaccination. The 2020 Guidelines provide additional information on testing and vaccination recommendations based on lifestyle and geographical location [7].

Nutrition for life

Nutrition provides the building blocks for normal, healthy growth and sets the stage for a healthy adulthood. The guidance of the veterinary professional is invaluable in this matter, enhancing the veterinary-client relationship, and building trust for future visits, including vaccination visits. Even before the first clinic appointment, the veterinary team can provide direction on feeding as kittens transition from nursing to solid food. To develop food texture experiences, it is ideal to expose kittens to both canned and dry food, in a variety of textures and flavors, particularly during the socialization period. This will facilitate acceptance of any necessary dietary changes during adulthood. When choosing a food, high quality, balanced kitten formulations are ideal, preferably sourced from a manufacturer who has veterinary nutritionists on staff and with high quality control standards for incoming ingredients and outgoing final products, demonstrating a commitment to safe, high caliber diets. As kittens transition to adulthood, a “first birthday visit” with a veterinary team member to assess body weight and body condition score will help keep kittens on track. This visit is a perfect opportunity to assist the caregiver in transitioning the pet to adult food, promoting a better understanding of weight management, and enhancing the veterinary-client patient bond. It can also provide an opportunity to ensure all booster vaccinations are up to date, or to pre-book appointments to meet upcoming vaccine needs.

The kitten friendly visit: forging lifelong bonds

In 2012 the International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM) and American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) developed the Cat Friendly Clinic and Cat Friendly Practice Programs, respectively. Since then, “Cat Friendly” care has become a well-established principle in feline medicine around the world, and the concept applies to kitten visits as much as any other age group. The domestic cat’s socialization period starts around 2 to 3 weeks of age and ends around to 9 to 10 weeks of age [10], and this is a crucial period in which to develop good experiences around the veterinary visit. With such a short window of opportunity, it is essential that a kitten has a positive experience during a clinic visit. With vaccination protocols starting at 4-6 weeks of age the veterinary team has perhaps only one to three opportunities to create a positive Cat Friendly experience. Veterinary visits should include Cat Friendly interactions, with plenty of positive reinforcement, conducted with minimal restrictive handling or restraint, setting the stage for the patient and owner’s comfort with future veterinary visits and forging a stronger veterinary-client-patient relationship. Development of Cat Friendly care can start with small changes in the clinic [11], and both the ISFM and AAFP offer programs to assist with this. Individuals within a practice may also elect to become “Cat Friendly Certified” through the AAFP.

Even minor changes will make a difference in the veterinary experience for kitten, caregiver, and the veterinary team (Table 2). Kittens are busy and playful, so to complete a physical examination and administer the necessary vaccinations and other medications the veterinarian must be creative in interacting with kittens. Forceful restraint and aggressive handling just to “get the job done” or because the “kitten won’t cooperate” will set everyone up for failure during future visits. Human impatience can contribute to so-called “fractious” behavior. The way ahead is to take a patient-focused approach that seeks methods to put the kitten at ease, distracting with food, toys, head-rubs and other accepted forms of positive reinforcement (Figure 3). With appropriate diversions, administration of vaccines at the recommended injection sites (Figure 4) is possible.

Table 2. Suggestions for Cat Friendly care principles as applied to each step of the veterinary visit, starting at the caregiver’s home. These are essential to providing positive, rewarding veterinary experiences early in the cat’s life.

| Location | Suggestions |

|---|---|

|

At home

|

• Choosing the right cat carrier, including an easily removeable lid

• Training the cat to use the carrier

• Preparing the cat and carrier for travel

• Following safe automobile travel practices

|

|

Reception room

|

• Cat-only waiting zone or cat-only appointment hours

• Consider putting cat and caregiver into examination room on arrival

• Elevated tables for carriers to sit on

• Blankets sprayed with pheromone to cover carriers

• Minimize waiting times

|

|

Examination room

|

• Longer appointment times: >30 minutes

• Place carrier on floor with door open

• Allow the cat to come out of the carrier on their own

• If patient will not voluntarily come out of carrier, remove, or open carrier lid and gently lift patient out. Avoid pulling, shaking and other aggressive maneuvers that will frighten the cat.

• Utilize warm, pheromone-sprayed blankets to lay under and over cat during examination (Figure 2)

• Patients too frightened for the examination should receive anxiolytic and sedative medications

|

| Injections & blood sampling |

• Utilize toy and food distractions whenever possible

• Consider anxiolytics, analgesics and/or sedatives

• Eliminate restraint methods including scruffing, pinning, limb restraint and muzzles

|

Conclusion

Kitten vaccinations are essential to ensuring appropriate immunity to prevalent and potentially harmful infectious disease. They are a key component of overall preventive healthcare for kittens, but equally as important, they provide interaction opportunities during which the veterinary team can set the stage for affirmative experiences and positive future interactions. Employing Cat Friendly principles while preventing disease through appropriate vaccinology based on patient needs sets the foundation for future feline wellness.

References

- Stone AE, Brummet GO, Carozza EM, et al. 2020 AAHA/AAFP Feline Vaccination Guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2020;22(9):813-830.

- Casal ML, Jezyk PF, Giger U. Transfer of colostral antibodies from queens to their kittens. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1996;57(11):1653-1658.

- Claus MA, Levy JK, MacDonald K, et al. Immunoglobulin concentrations in feline colostrum and milk, and the requirement of colostrum for passive transfer of immunity to neonatal kittens. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2006;8(3):184-191.

- DiGangi BA, Levy JK, Griffin B, et al. Effects of maternally derived antibodies on serologic responses to vaccination in kittens. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2011;14(2):118-123.

- Day MJ, Horzinek MC, Schultz RD, et al. VGG of the WSAVA. WSAVA Guidelines for the vaccination of dogs and cats. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2016;57(1):E1-45.

- Levy J, Crawford C, Hartmann K, et al. 2008 AAFP Feline Retrovirus Management Guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. [Internet]. 2008;10(3):300-316. Available from: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=18455463&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks

- Little S, Levy J, Hartmann K, et al. 2020 AAFP Feline Retrovirus Testing and Management Guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. [Internet]. 2020;22(1):5-30. Available from: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=31916872&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks

- Westman ME, Malik R, Hall E, et al. Determining the feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) status of FIV-vaccinated cats using point-of-care antibody kits. Comp. Immun. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. [Internet]. 2015;42:43-52. Available from: http://pubmed.gov/26459979

- Westman M, Norris J, Malik R, et al. The diagnosis of Feline Leukaemia Virus (FeLV) infection in owned and group-housed rescue cats in Australia. Viruses 2019;11(6):503.

- Quimby J, Gowland S, Carney HC, et al. 2021 AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stage Guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2021;23(3):211-233.

- Rodan I, Sundahl E, Carney H. AAFP and ISFM feline-friendly handling guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. [Internet]. 2011;13:364-375. Available from: http://jfm.sagepub.com/content/13/5/364.short

Kelly A. St. Denis

MSc, DVM, Dip. ABVP (feline practice), Powassan, Ontario, Canada

Canada

Dr. St. Denis is a practicing feline medicine specialist, board certified with the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners in the specialty of feline practice. In her early career she trained in molecular biology and immunology before going on graduate from the Ontario Veterinary College in 1999. She owned and operated the Charing Cross Cat Clinic from 2007 to 2020, and has co-authored a number of practice feline guidelines, as well as being co-editor of both the AAFP Feline Practitioner Magazine and the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. Dr. St. Denis is a consultant on the Veterinary Information Network in feline internal medicine, and lectures internationally on all things feline. She is past president of the American Association of Feline Practitioners.

Other articles in this issue

Share on social media